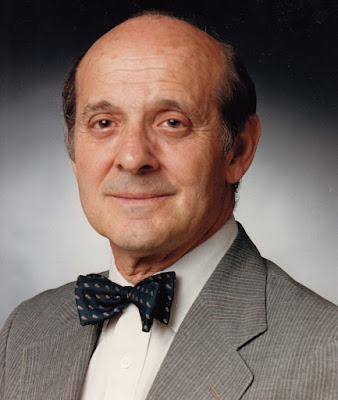

Ink & More, Always by the Barrel: David Starr 1922-2019…

Rising like a monolith above the plains of urban renewal in north downtown Springfield, The Republican stands watch. At one time, David Starr sat atop it all, the representative of the Newhouse publishing empire here in the Valley. But from his office at 1860 Main Street, was he standing guard or surveying an empire?

Thought not a native, he embraced the city as his own upon arrival in 1977. Still, his arc in Springfield is not without controversy. Starr’s influence in politics and the community, however, inflames passions on both sides of his paper’s editorial and newsgathering decisions. For better or worse, with him passes the end of an era in local journalism.

David Starr passed away last Monday. His death was announced in The Republican.

For those that benefited from his friendship and his ink, Starr was the consummate civic leader. For example, the Springfield Museums called him a “catalyst and a visionary” who “leveraged his considerable skills, influence and expertise to preserve and expand” the museums.

The Community Foundation’s Katie Allen Zobel noted that Starr was a charter member of the organization. He “left a deep and lasting imprint on so many of us and this organization,” she said.

To those not in his good graces—unionized staff, errant politicians, rival periodicals, noisy activists or wayward luminaries—Starr was, as The Valley Advocate put it in 1998, a “notoriously vindictive newspaper publisher.”

“He was a quiet and unassuming man who wielded a lot of power, sometimes for good journalism and civic causes,” recalled Natalia Muñoz, a former reporter for the paper.* “Other times he used the power of the press to please his friends.”

Libertarian critics accused him of protecting corrupt pols. Progressive media like The Advocate saw social needs buried and monied interests favored.

Starr himself was unapologetic about using the papers to boost the city—and happenings he personally supported. But he vehemently denied untoward political meddling.

“We take stands and people who take the other side don’t like us,” he told Commonwealth magazine.

The issue was not necessarily the editorial board’s positions, which Starr and his successors controlled per filings in a labor dispute.

Starr could never convincingly dispel notions that he bent news coverage to his will, too. Rather, his paper seemed, as Commonwealth noted, “a member of the club.”

“It is the government and the city’s only newspaper [that are] in charge, so what would normally be the critic and the adversary is not,” Robert Markel, a former Springfield mayor, told the magazine.

David Starr was born on August 1, 1922 in New York. According to The Republican, he started in newspapers by delivering them. After serving during World War II, he signed on as a reporter with the Long Island Press, which the Newhouse family owned.

He married his wife Peggy in 1943. She, their two children and two grandchildren survive him.

Starr worked for the Press and other Newhouse papers, including The Star-Ledger. In 1977 he arrived in Springfield as publisher of the Springfield Newspapers, which published the afternoon The Daily News, Morning Union, and The Sunday Republican.

The Daily News and Morning-Union merged into the Springfield Union-News in 1988 before becoming simply The Republican circa 2001.

Advance Publications, The Republican‘s parent company, did not reply to a request for comment. But Starr appeared close to the Newhouses.

“Dave was a great teacher because his training emphasized the importance of core concepts: fairness, credibility and respect for readers,” Steven Newhouse, co-president of advance, told The Republican.

The paper’s editorial board waxed hagiographic about Starr. Yet, other publications writing about Starr and his paper, usually found employees willing to counter the party line, if without attribution.

“He certainly wasn’t an evil publisher—even as he nickeled and dimed union members,” Muñoz dryly remembered.

The Republican’s Sunday editorial said Starr’s “impact cannot be overstated.” Perhaps not, but the phrasing allows sharply differing views.

Starr’s appointment had been a change. Traditionally, Springfield Newspapers’ leadership came from within.

Virtually since Samuel Bowles, III (pictured) founded The Republican, its leadership had come from greater Springfield until Starr’s appointment. (via wikipedia)

In the paper’s obituary, Executive Editor Wayne Phaneuf recalled, “When Dave came to Springfield, there was a lot of trepidation among the newspaper staff and community because he was the first outsider to take the helm in more than 150 years.”

The incumbent publisher, Sydney Cook, became president of Springfield Newspapers, a title Starr would hold two decades later. Starr retained a senior editorship overseeing the Newhouse wire service.

After arriving, Starr quickly took interest in Springfield. He headed Springfield Central, a civic organization, for years and promoted culture and development. This was his way.

Weeks after moving to Springfield, then-New York Mayor Abraham Beame praised Starr for his time at the Long Island Press and its impact on Queens’s Jamaica neighborhood.

“One lesson I am taking with me to Springfield,” Starr said according to a Newhouse wire report. “Problems can be solved.”

Starr’s civic efforts in Springfield attracted notice, too. In 1983, The New York Times observed the “unusual coalition of business, government and the press” behind Springfield Central’s then-privately funded endeavors. Representing the press was Starr.

Starr’s local cultural endeavors—Symphony Hall renovations and reviving Citystage—had led to national and state cultural appointments. Marketing Springfield’s Dr. Seuss connection practically became an obsession—and it bore fruit. Indeed, proper accounts of the Seuss memorial or transmogrifying the Connecticut Valley Historical Museum into the Seuss Museum mention Starr.

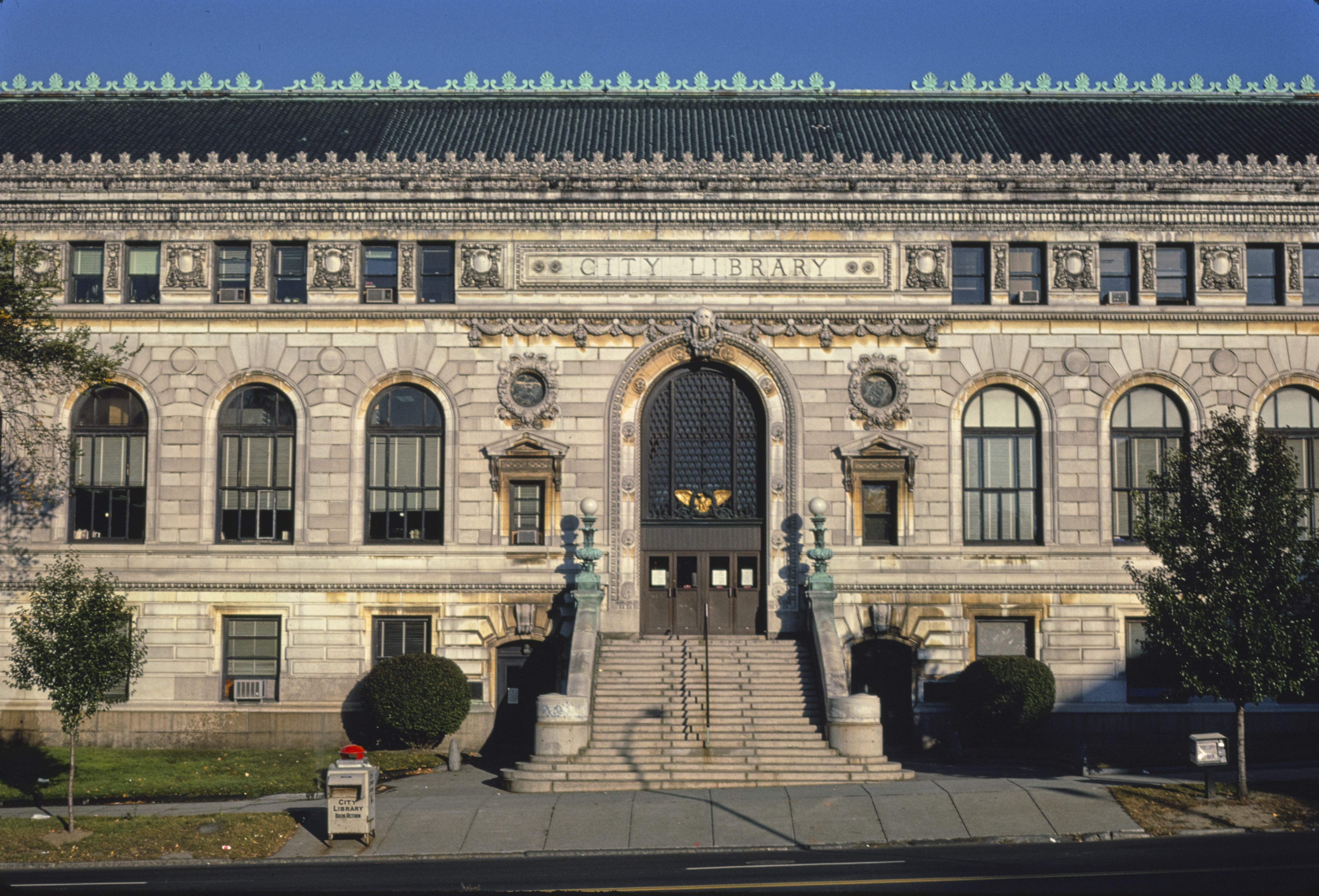

Springfield Central Library (via wikipedia)

Still, there is a counter-narrative. Starr’s approach could be heavy-handed. For example, while he served on the Springfield Library and Museum Association (SLMA) board, the museums thrived. City libraries, which the SLMA operated, often went without.

Sheila McElwaine, a library advocate and later a Library Commissioner, criticized Starr and “his clique” at the SLMA. About 15 years ago, following shakeups and downsizing, McElwaine said, the association planned to close and sell branch libraries including the Forest Park branch near her.

“They actually did sell the Mason Square Library which had just been renovated with public funds,” she said in an email. “What kind of newspaperman would intentionally decimate the library system of its city?”

The association had claimed city budget cuts prompted this, but Starr later muddied that timeline in a deposition. The Advocate, writing about that 2006 deposition, described Starr bristling at questions about library cuts and the sale of the Mason Square branch.

Yet, taking on the SLMA could mean taking on the paper.

During the 1990’s, Pioneer Valley Project, a faith-based community alliance, sought access to and accountability from the SLMA. They enlisted City Councilor Barbara Garvey to help. In 1997, an editorial blasted Garvey’s efforts as “heavy-handed interference” and a “witch-hunt.”

“The more I helped them, the worse the situation got with me,” she told The Advocate in 2000.

Charles Ryan circa 2007 (via Urban Compass)

After years of litigation and community outcry, the city took over the libraries and seized the Mason Square branch via eminent domain. Charles Ryan was a key player and it fueled his return to the mayor’s office. However, this was well after his own relationship with Starr had fractured.

“If you cross David Starr,” Markel told The Boston Globe in 1995 shortly after losing reelection, “there are consequences. Everyone in this town knows that.”

Starr told The Globe, in a story about his influence, such charges of retaliation were “sour grapes.” But reporters anonymously told The Globe the newsroom felt pressure to toe the Starr’s line.

But despite deep dives into courthouse patronage and solid Control Board and mafia coverage, charges of bias linger.

Both The Advocate and The Globe have recounted then-candidate and later Councilor Mitch Ogulewicz’s claim that Starr admitted to plans “manipulate and cajole voters” to support favored candidates. Starr vehemently denied it.

After The Boston Globe revealed then-Hampden District Attorney Matthew Ryan’s ties organized crime, Starr and his paper faced accusation of protecting an ally.

Starr’s deposition, The Advocate reported, noted frequent and private meetings with city officials.

Markel’s loss came amid a push to legalize casinos, which Starr’s papers supported. Voters rejected casinos, but elected Michael Albano. His maladministration brought federal indictments of city staff and the Finance Control Board. Starr’s papers backed Albano almost to the end. That included Albano’s own megaproject: a baseball stadium.

“The stadium battle was equally hard-fought–and the Union-News editorials just as pointed, even personal, with opponents castigated as ‘obstructionists’ and ‘naysayers,’” Commonwealth observed. Critics claimed, the paper did not review the project’s merits for its readers.

But what separated this project from others was the wielding of city power and money. Residents formed Citizens Action Network to successfully push back.

Judge Constance Sweeney ruled the land taking for the project was illegal.

As elsewhere, however, assessments of the reporting were split.

Critics had mixed feelings, too, admitting coverage was largely fair. The issue was tone and the independence of analysis. Similar critiques would arise during the 2013 casino debate.

City library supporters like McElwaine complain, reasonably, that Starr bullied pols and suburban benefactors to do his bidding. Yet, it is hard to imagine the investments in the Quadrangle’s cultural offerings—libraries aside—without Starr’s fundraising efforts.

As for the paper itself, even critics have supported its survival. Indisputably, The Republican and its forebears have been key to the Land of Springfield—just like Starr.

But virtually all of Starr’s reign came during the heyday of newspapers. Changing media economics, not age or retirements, loosened the paper’s grip on 36 Court Street. Advance set up parallel nonunion newsrooms for their papers’ digital websites, effectively competing with their tree-bound cousins. Many Masslive scoops actually appear in the paper.

Advance has also experimented with less than daily publication of some papers. Youngstown, Ohio’s independently-owned daily will soon shut down.

The Springfield Republican, in an older form, has a brief cameo in Sinclair Lewis’ 1935 novel about a fascist takeover of America, It Can’t Happen Here.

With Starr passes an era of Valley media. However flawed and now diminished Starr’s publications were, the Springfield region still has a preeminent, convening media outlet. But for how long? Post-Starr, life without it can happen here and very well may.

David Starr was 96.

(via Tommy Devine’s blog)

*WMassP&I Editor-in-chief Matt Szafranski has appeared as a guest on Muñoz’s WHMP show.