The Trans-Commonwealth RR: Is a New Day Dawning for East-West Rail?…

The Trans-Commonwealth Railroad is a series on the challenges and efforts to connect the length of Massachusetts by rail.

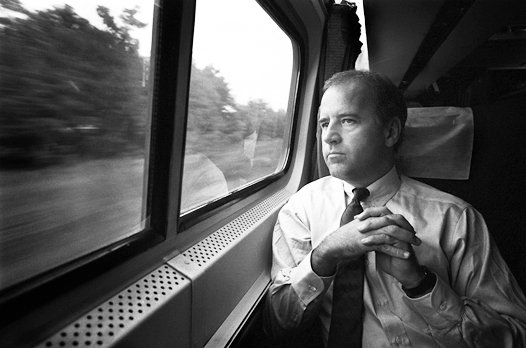

Despite officials in 413 mashing the accelerator as if on a clear stretch of Pike, East-West rail entered 2021 with only muted optimism. Governor Charlie Baker, hardly a proponent, had agreed to a study. Springfield’s US Representative Richard Neal ascended to one of the most powerful position in Congress. Joe Biden, Amtrak’s passenger of the year for nearly five decades, won the 2020 election. Yet, headwinds loomed larger. Republicans looked set to hold the US Senate and the study hardly opened the throttle on progress.

As January progressed, there were shifts for the better. Democrats won control of the US Senate, not only improving Biden’s hand but making Chuck Schumer, a son of America’s most transit-dependent city, majority leader. As many had anticipated, Baker’s study reached some unhelpful conclusions. However, the governor opted not to veto language in a last-minute bond bill that could pave the way for work on the East-West corridor.

“It is a significant achievement and a significant moment for everybody who has worked on this project over the years,” Senator Eric Lesser said in an interview earlier this month.

Establishing regular service between the 413 and the Hub will be a monumental task. Decades of underinvestment in the old Boston & Albany line, now split between CSX, a freight railroad, and the Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority, have left limited capacity to add trips. The ancient track geometry, dating to at least the Grand administration, is curvy and hilly, limiting speeds.

One Amtrak train does operate between Boston and Western Massachusetts locales as part of service to Chicago. The pandemic has temporarily reduced it to less-than-daily service.

Lesser and others have said that the final study contained few surprises. Supporters note that the study, which the Massachusetts Department of Transportation released on January 4, projects low passenger volume. Such projections could imperil federal funding.

“It makes you wonder what MassDOT’s motivations were,” said Lesser, a Longmeadow Democrat. He observed that the agency looked at the Hartford Line, a Connecticut rail service between Springfield and New Haven. However, the population of Greater Hartford pales in comparison to that of Boston.

“Meanwhile there are all sorts comparable line they did not analyze,” he said.

Lesser said that better comparators would be rail lines that link Chicago and San Francisco to smaller cities like South Bend, Indiana and Stockton, California.

Nevertheless, the study hardly slams the door. For example, it offers several options for service and construction. A brand new Shinkansen or TGV-style line is unlikely, absent a humungous realignment of federal policy—to say nothing the years it would take to build. Yet, simpler construction could facilitate service, perhaps well before Biden rides an Amfleet coach into the sunset.

President Biden developed an affinity for Amtrak as a senator, traveling back to Delaware daily, so he could be with his sons. (via Twitter@JoeBiden)

For example, some of the alternatives contemplate additional rights-of-way, namely between Springfield and Worcester, for a not-implausible $1.5 billion. Re-installing double-tracking for the line’s entirety west of Worcester is likely in any plausible scenario.

One of the challenges, however, is fitting the project into the broader rail line. The MBTA already operates commuter trains between Boston and Worcester. Various infrastructure improvements, including additional track, rebuilt stations, modernized signaling and reconfigurations at Boston’s South Station will be necessary to squeeze in more service to Springfield, Pittsfield and maybe Albany—assuming the Empire State wants to play ball.

Some engineering or other technical work could see some initial funding thanks to the $50 million in the transportation bond bill. While it will still require Baker—or if this drags out, his successor—to release the funding, his decision to not veto the money is a pleasant surprise.

Baker surrendered on the study long ago, but is the rail revolution now upon us? (created via WMP&I, Architect of the Capitol & Google image search)

Because the legislature passed the bond bill hours before the new General Court took office on January 6, it would have bene impossible for the body to override his vetoes. His Excellency has never waxed enthusiastic about the project—his acquiescence to the study came months before he faced voters in 2018—and supporters braced for a veto. But none came.

Once released the funding could prompt several outcomes, including some kind of service sooner rather than later. Despite being generally skeptical about working with Amtrak, the study did not rule it out as a partner. This is critical as Amtrak—but neither the commonwealth nor the MBTA—have trackage rights on CSX’s routes. While negotiations with both Amtrak and CSX will be tedious, service might happen faster than completion of significant construction.

Longer-term, hope is emanating from Washington. Neal, who chairs the House Ways & Means Committee, has pointedly supported East-West rail. He was bullish on a big infrastructure package even before Georgia Democrats Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock won their runoffs, delivering Dems the Senate. Now Neal has more space to ensure funding exists to stitch the commonwealth’s east and west together with track.

Senator Schumer, now Senate Majority Leader, has his own infrastructure wish list. Among the items is a new rail tunnel under the Hudson River. However, such projects only compliment East-West rail (Springfield already has more daily trains to New York than Boston). Democratic control of Washington likely assures these projects will not suffer from competition.

Returning to South Bend, Pete Buttigieg, Biden’s Transportation nominee, has echoed his boss’s support for rail service. While his confirmation was probably never in doubt even before the runoffs in Georgia, Buttigieg made clear he would be an ally on the issue.

“I enjoy long train trips, as well as short ones,” Buttigieg told a Senate committee last week. “I think Americans ought to be able to enjoy the highest standards of passenger rail service.”

Back to the future with Buttigieg and Lesser…from flying with Obama to Ridin’ with Biden along the rails? (via Lesser campaign)

Neal may not be the only East-West rail advocate buzzing in Buttigieg’s ear, should the Senate confirm him. Lesser and Buttigieg overlapped at Harvard and worked together on former President Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign.

It may be too early to break out the briefcase to commute between Boston and Springfield. Still, the last month does offer hope to a project that has plodded along for years. East-West rail was a central plank in Lesser’s 2014 campaign platform. The issue goes back further to the Northern New England Intercity Rail Initiative study and the advocacy of entities like the Pioneer Valley Planning Commission.

The PVPC had pressed for North-South rail between Greenfield and Springfield. While currently limited due to the coronavirus, supporters have touted the Valley Flyer’s pre-pandemic success. Both it and Connecticut’s Hartford Line would also tie into East-West service.

From Biden’s win—and now inauguration—to Neal’s chairmanship to the bond bill, everything signaled a new day had arrived, Lesser observed.

“It’s just a huge game changer,” he said.