Chris Murphy on Navigating the Boulevard of Broken Impeachment Trials…

HARTFORD—Impeachment, remember that?

Though it ended nearly two weeks ago, its ramifications are ongoing and uncertain. In the death throes of the nation’s third impeachment trial whose outcome was clear, there was twist. It was not bipartisan. Utah Senator Mitt Romney, late of Massachusetts cast the lone Republican vote for impeachment. It was just one a few connections Connecticut Senator Christopher Murphy had to overall drama.

Both of Massachusetts’s senators voted to convict, but had to return to campaign trail. South of the border, Murphy returned to the Constitution State to debrief constituents about impeachment. The day after the Senate acquitted Donald Trump at the University of Connecticut School of Law campus here, Murphy spoke about the process, the state of the Senate and Washington, politics and Romney’s vote.

Romney “doesn’t want his name on the list of arsonists,” Murphy said. Murphy added later, “I fear that my colleagues in doing this”—not hearing from witnesses and acquitting Trump—”failed to protect the Republic.”

Like all Democratic senators, Murphy voted to convict Trump for abuse of power and contempt of Congress. Romney only joined Democrats on the former. That charge refers to Trump’s haranguing of Ukraine for an investigation of the Biden family—or at least a public declaration thereof—in exchange for congressional appropriated aid.

The format of Murphy’s event consisted of remarks and audience questions posed by Douglas Spencer, a constitutional law professor at UConn. Though, his remarks largely mirrored those he gave on the Senate floor the day before.

Murphy in his sophomore term as a state rep in 2001 (via Meriden Record-Journal)

Murphy, expressive and energetic, projects a small-d democratic earnestness discussing the trial’s implications for the constitution, history, and the republic this. Only under interrogation does he fall back into a suspicious, pensiveness to absorb a question.

Now in his second term in the US Senate, Murphy, 46, rose through Connecticut politics winning races Democrats seemed doomed to lose. That included stints in the US House and both of chambers of the Connecticut legislature starting in 1998. Before that, he served in Southington government. Today he is a Democratic tentpole in Connecticut alongside his Senate colleague Richard Blumenthal and the all-Democratic state officeholders.

Once the Senate’s youngest member for a Congress, Murphy described how his early life serendipitously overlapped with events surrounding Watergate.

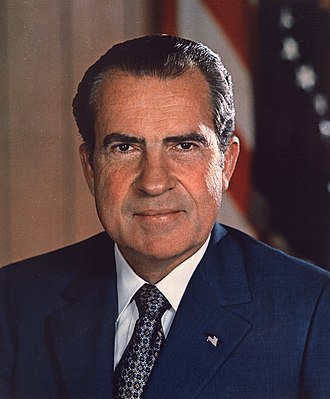

In his remarks, Murphy noted that his birth came only weeks after Alexander Butterfield revealed then-President Richard Nixon’s recording system. Other events like the Senate’s subpoena of the tapes, the Saturday night massacre and ultimately Nixon’s resignation took place in his infancy.

However, Murphy said his parents, who had voted for both parties over the years, were deeply disturbed by Nixon’s behavior. They inculcated an expectation for better in their children, he said.

Was he a crook? Either way, his actions greatly troubled voters like the Murphys. (via wikipedia)

“What mattered when they were choosing candidates is whether you were honest, whether you were decent, whether you were running for office and serving in office for the right reasons,” Murphy said.

That does not seem to be the case today, he argued, saying that Republicans are behaving in a way to defend party that they would not 45 years ago.

The exception was Romney, whom Murphy had befriended during a trip to Israel last year. He admitted to being “a little choked up” by Romney’s speech about faith and how it informed his decision to convict despite the political and personal risks it might entail.

Murphy’s had a connection to the actual events precipitating impeachment, too. Murphy was among the senators urging Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to reject Rudolph Giuliani’s demands for investigations. Thus, Murphy’s name came up multiple times during House impeachment managers’ arguments.

Since Murphy’s impeachment debrief, he and Republican colleagues have again met with Zelensky to assure him support for his country remains bipartisan.

Speaking to reporters after the event, Murphy said that his experience working on Ukraine policy had given him a somewhat stronger view about the situation.

“I think that Ukraine sovereignty is really important to US national security, and I think we’ve compromised their sovereignty by dragging them into this mess,” the senator said.

President Zelensky walking down the line that divides him somewhere in his mind about how strong US support is? (via Reuters/al-Jazeera)

Impeachment laid bare the system’s vulnerabilities should one branch, in this case the executive, simply refuse to cooperate. Republicans accused Democrats of rushing the process by not seeking court orders even as Trump and his lawyers were arguing in court that Congress had no right to subpoena the executive.

Murphy held out some hope that perhaps Congress can pass laws that avoid this problem eventually. How to assure that subpoenas are dispensed with in an expeditious matter, is the central question. However, Murphy later told reporters the impeachment air may need to clear before those discussions can begin.

Questions varied on and off impeachment directly throughout the evening, though Murphy fielded questions about the Chief Justice handled things—well enough—and how some Republican colleagues envied Democrats’ freedom to state the obvious during their comments. Still, many Republicans, Murphy noted, did not dispute the facts the House presented. Most just asserted these did not mandate removal.

On an issue tangential to the impeachment, but ultimately tied to Ukraine policy, Murphy discussed how the United States is woefully unprepared to counter international threats of today. The issue came up in a question about whether in 2012 Romney, then his party’s nominee to defeat President Barack Obama, was right about Russia’s threat.

Murphy noted that at the time international terrorism, not state actors using disinformation, was the major threat then. Now it is propaganda and lies being blasted through the Internet influencing people and radicalizing others. Consequently, we fight today’s conflicts asymmetrically and do so by choice.

“Because we still think we protect this country with military power alone,” he said. Murphy went on to note how many times larger the military defense or intelligence budgets are than the State Department’s is. In other words, the US is under-investing in non-military ways to resolve problems.

“We have to build up our capacities to fight all of these low-cost tool kits that countries like Russia or North Korea have to screw with us both inside the United States and in allied countries,” Murphy said.

However, getting there will not be easy. Murphy described conversations with some—not all—Republican colleagues who agreed that many of Trump’s actions are wrong and that he may even be a threat to democracy. However, they telegraph a graver threat: an unelected bureaucracy disagreeing with the president. Clearly, the thinking goes, these people must be liberals or Democrats as no self-respecting conservative would work in government.

The media is just as bad, giving Trump, a Republican president, no chance and the impeachment trial was simply a culmination in this conspiracy. Trump is only the latest target of the left.

“That theory is crazy,” Murphy noted. “But I think in service of trying to repair the damage that’s been done to the country, we need to understand where they’re coming from and we need to put ourselves in their shoes, and not just assume that they are all just as corrupt as President Trump.”

For his part, Murphy told reporters he hoped that explaining his vote would help people see that he did not vote to convict just because of he dislikes the president. Rather, he pointed to his willingness to take on former President Obama to show that he had been consistent in standing by his values.

At his alma mater in one of the most Democratic parts of the country, Murphy found a friendly audience. But with the conclusion of impeachment’s convulsions, here the air felt thick with doubt, if not as pea soup-thick as the Senate’s mistrust-laden air is.

The conversation concluded with Professor Spencer sounding a hopeful note a US senator explaining his actions directly to constituents. Before that, though, he asked Murphy how he remained optimistic.

As a congressman, Murphy represented Newtown on the date the Sandy Hook shooting. The Senate’s rejection of background legislation was a depressing low in his political career. Since, he has noticed shifts even among Republican senators who are talking about how to pass a background check bill. Murphy attributed his change to the gun safety movement that has developed and has preserved despite setbacks. In the end, such movements can prevail.

“That’s the faith I bring to this job and the faith I will continue to bring this job,” Murphy said.