Bending the Arc of a City’s Moral Universe: Michaelann Bewsee 1947-2019…

The power is yours, and it would be if Michaelann Bewsee, pictured in 2015, had her way. (via Twitter/@SpfldMAElection)

Injustice had no greater foe in the City of Springfield than Michaelann Bewsee.

After co-founding what would become the city’s feistiest community organization, Arise for Social Justice, Bewsee contributed to innumerable battles for equality and fairness. She embraced the city’s cultural mosaic without losing sight of its individual pieces. Blacks, Hispanics, LGBTQ people, the physically impaired and countless others had an ally in her.

In the 1980’s, when Arise was founded amid debate of welfare cuts, she advocated for tenants. She backed needle exchange and ward representation in the 90’s. In the new millennium she was with the tent city for the homeless and vehemently opposed biomass.

Ultimately, Bewsee saw the impact on the individual level.

Michaelann Bewsee, fourth from right, at a vigil for a homeless man who died of exposure in 1987. (via Masslive/Republican)

“I see all of our neighborhoods being disrupted because people cannot afford to pay rents,” she told The Springfield Union-News in 1989. The comment came amid a push for rent control as the Western Mass director for the Massachusetts Tenants Organization. “People are becoming transient in their own community,” she added.

Bewsee died Thursday after a battle with lung cancer. A fund has been set up to help finance funeral expenses.

The disease had prompted her retirement from Arise last year, but she had continued to engage.

“I’m not going anywhere,” she assured in an interview last October. She endured. As recently as May she was reminding state officials about Springfield’s pitiful air quality during a hearing on defining biomass as alternative energy.

But her human side beamed, too.

In 2006, The Valley Advocate put it succinctly. “In a city filled with poverty, pimps and posturing politicians, Michaelann Bewsee and her Springfield-based organization, Arise for Social Justice, are refreshingly genuine, willing to fight hard for the disenfranchised, and doing it with honesty, dignity and smarts,” the alternative wrote.

A wave of remembrances from organizations, politicians, battle-hardened activists and social media admirers have flooded out. She nurtured generations of activists—and a few pols—some of whom became like family.

At-large Councilor Jesse Lederman, a close friend, urged “all to pause and recognize the life of this remarkable Springfield resident, mother, Activist, and friend.”

“Michaelann Bewsee was a relentless advocate for people and causes that society too often ignored,” he said in a statement. “She was endlessly compassionate, fiercely committed, and uncorrupted in her goal to seek justice.”

Michaelann Bewsee was one of the key figures that built Arise for Social Justice into a force for the marginalized and disenfranchised in Springfield. (via arisespringfield.org)

Though a committed general in the fight for justice, as Lederman and others observed she was never prideful about it. She earned accolades, but shared credit with the leaders that marched with her. How could she bask in victories? There was always another battle to wage.

“She was always there for our members fighting to keep their homes. She firmly believed that housing needs to be a human right and fought alongside and with all of us,” Springfield No One Leaves, an anti-eviction/anti-foreclosure group, wrote on Facebook. The statement thanked Bewsee for her early support, via Arise, of No One Leaves.

Michaelann Chapin Bewsee was born in Springfield on December 21, 1947 to Emery and Ann Marie Bewsee. She came from working class family and attended Cathedral High School. Her activism began young. Bewsee sang in the high school choir, but also flipped pancakes for a Black Panther Party breakfast program aimed at poor children.

Activities like this would brand Bewsee a radical, and she was, in her way. But it was the tangible consequences that animated her. She wanted answers to big questions about why poverty persisted in the wealthiest nation in the history of civilization. But it was just as important to her to feed the poor, a column in The Daily Hampshire Gazette explained last year.

In the 1980’s, around Arise’s founding, Bewsee was a point person for the Affordable Housing Alliance. She tangled with city officials, including then-Mayor Richard Neal, who had named her to a housing task force she, at times, criticized. Part of the concern was the lack of renters on the body.

“We were never happy with the make-up of that task force,” Bernard Cohen of Affordable Housing Alliance told The Union-News. “There is only one tenant on it, that’s Michaelann.”

City officials urged patience. In the end, Bewsee praised the report as “excellent,” though hoped to see more on condo conversion and links between upper income and affordable housing.

Over the years, Bewsee would lend her support to candidates like Lederman and, a few years earlier, Amaad Rivera. But she dabbled in politics herself. She ran for City Council in 1987 and toyed with a mayoral run in 2015. For a time, she blogged.

Michaelann Bewsee with her children and grandchildren. (via Valley Advocate/Bewsee family)

Along the way, Bewsee had two daughters, Jessica Bewsee and Emily Konstan. Bewsee’s children, brother, two sisters, and two grandchildren survive her.

“I think what she thought was her activism was so important because of her children,” Jessica Bewsee told The Valley Advocate. “She wanted a better place for her children and grandchildren and for everybody’s children.”

While tough as nails, Bewsee expressed some empathy even for erstwhile opponents. When an Agawam woman put forward a nonbinding question to abolish the welfare system, Bewsee did not dismiss her out of hand.

“She sounds like she is someone frustrated with not having her own needs met. She shouldn’t turn against welfare recipients, who are at the very bottom rung,” Bewsee told The Union-News.

Though Bewsee’s activism carried over to issues near and far—she opposed recent wars and traveled to Nicaragua on a humanitarian mission—her heart remained centered on Springfield. She slammed bigoted statements from city officials or wryly commented on the upward falls of political hacks.

When Francis Keough—somehow—became the head of Friends of the Homeless, she marveled at how someone so “unsympathetic” to the homeless had ascended to that position.

“The Friends of the Homeless must feel pretty invulnerable to criticism,” she said at the time.

Michaelann Bewsee following a biomass hearing. She was a common sight at 36 Court Street whether attending a hearing…or occupying the mayor’s office. (WMassP&I)

In the 1990’s, efforts to change the city’s electoral system were heating up. In 1959, the ethnically varied, but blindingly white electorate abolished a ward-based Council in favor of a nine-member at-large Council.

Bewsee and Arise sought and established alliances of all stripes to bring back ward seats and make the Council more representative.

“If the opportunity were there to vote for candidates that would hear our concerns, we would have healthy competition,” she said in 1997.

For the most part, she was right, though the ballot question failed that year.

“We’ve been building this body of knowledge that’s going to take us through this campaign and into other campaigns,” Bewsee told The Valley Advocate before the 1997 vote. “If there’s one thing that’s really clear, [it’s that] whatever happens November 4, it’s not over.”

Once ward representation gained approval a decade later, it did change city politics. Turnout remains grim, though competition is relatively high. An open ward seat this year attracted four candidates and almost every ward seat has seen an incumbent challenged.

.@Melvinstweet thanks @michaelannb for work on getting ward representation, via which he got elected. #spfldpoli

— Matt Szafranski (@MSzafranski413) June 25, 2015

Perhaps more to the point, issues that rarely got an airing, let alone approval—from police oversight, residency, immigrant protections and environmental justice—now pass by wide majorities.

The biggest of these was biomass. When Palmer Renewable Energy’s carbon-tastic permit first swept through the all at-large Council, Bewsee became a key figure in the drive to stop it. While never abandoning old issues, climate and the environment maintained a larger share of her attention.

The poor, she observed over the years, bear a disproportionate share of environmental degradation, including climate change.

“Your regulations are not strong enough,” Bewsee insisted at one meeting in reply to assurances public health was not at risk.

Following ward representation, a supermajority of councilors voted to void the permit. When Palmer Renewable, supported by the administration, decided a permit was unnecessary, Bewsee appealed to the zoning board of appeals (and won) and remained a litigant in the Land and Appeals courts.

Bewsee traveled to Boston, to observe appellate arguments. Later, she stood on the street, not far from the courthouse, dwarfed by Boston’s downtown canyon of buildings, reflecting on the process as she smoked a cigarette.

The Appeals Court turned her back. Still, victory took everything the developers could throw at a short and slight Springfield mother of two. Nearly four years later, the plant remains unbuilt. Its backers face new legal hurdles.

There were other theaters in which she fought. Bewsee pushed the city to appoint a climate coordinator. She, Bishop Timothy Paul, and Rev. Talbert Swan, II signed a letter opposing the appointment of Robert McFarlin as police commissioner. McFarlin, who once sued Arise, was allegedly on the fast track. Mayor Domenic Sarno picked John Barbieri shortly after the letter. Injustices at and emanating from Pearl Street were a frequent concern of Bewsee’s throughout her career.

Not every battle ended with victory. Yet, there is still no biomass plant. Springfield’s Council is more representative of the city. McFarlin retired.

There are still cold, hungry and needy people in Springfield. If Bewsee could not always minister to them herself, she ensured the least of Springfield were not hidden, forcing the City of Homes and its residents to see that they live.

“Michaelann Bewsee created paths when there seemed no way, she created hope when we were filled with despair, she was tenacious when so many were tired, her work leaves us all better and her loss leaves the city a little less just,” former City Council Amaad Rivera said on Facebook.

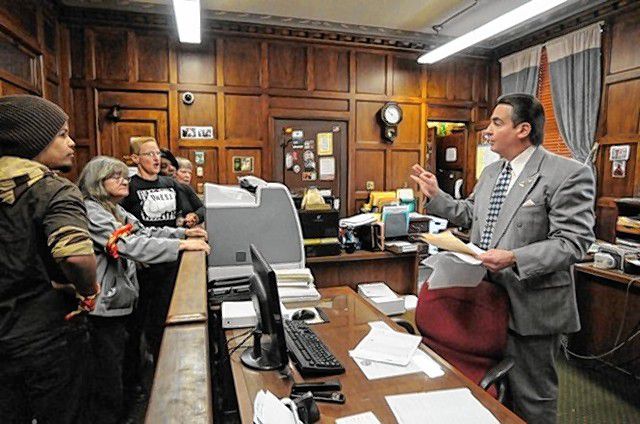

Bewsee and activists confront Mayor Domenic Sarno (via Valley Advocate/Bewsee family)

Reflecting on the handover of Arise to Tanisha Arena, Bewsee said the organization remained small on purpose.

“We always want to be the kind of place that a poor person can walk in the door and feel at home,” she told The Republican. There were few groups like Arise in Springfield when it organized in 1985. From nothing, it evolved into a force politicians, decisionmakers, mayors, developers and their well-heeled lawyers, could not ignore.

No One Leaves observed her “fight for human rights will live on through all of us that you have touched.”

Indeed, in her retirement interview, Bewsee warned, “I don’t want city councilors and elected officials to stop being afraid of me just yet.”

They still shouldn’t stop.

Michaelann Bewsee was 71.

(via Valley Advocate/Bewsee family)