A Mayor Called Sue(d): As Legal Battle Lumbers, Pressure outside Police Case Grows…

A Mayor Called Sue(d) is an occasional series on litigation over the Springfield Police Commission

The Police Commission litigation between the Springfield City Council and Mayor Domenic Sarno gingerly advanced this week as both parties filed post-argument briefs. Neither side raised any groundbreaking new theories during last week’s hearing. Plus, Judge Frank Flannery asked no questions signaling whether the Council’s Police Commission ordinance is valid or not. Thus, the new papers functioned something as a fresh round of barbs directed at the opposing side.

However, as the court was processing the documents, activists in Springfield put pressure on City Hall in a different way. Pioneer Valley Project (PVP), a community and civil rights group, and the Springfield NAACP called for the United States Department of Justice to impose a consent decree on the Springfield Police Department.

Last summer the Department of Justice, working through its Civil Rights Division and the Massachusetts US Attorney’s office, released a scathing report about the Narcotics Bureau at Pearl Street. It found persistent police misconduct and shoddy efforts from brass to correct it.

The report dovetailed with the wave of demonstrations that swept Springfield and the country after Floyd’s death in Minneapolis. Among the demands local groups like PVP and the NAACP had were the implementation of the Police Commission ordinance. Although the Council ordered its resurrection in 2016, Sarno ignored the new law and deemed it a dead letter. He kept the panel in the legislative tomb in which the Control Board had buried it back in 2005.

The PVP and NAACP’s call for a consent decree comes amid growing frustration with City Hall and Pearl Street’s alleged outreach on police matters. In a press release, the groups claimed that the city did not implement any proposed changes until after PVP and the NAACP issued public records request. The groups aired their demand publicly at an event at City Hall Thursday.

After initially mirroring the demands of national George Floyd protests, local activists zeroed on issues specific to Springfield. (WMP&I)

Even so, PVP and the NAACP’s release adds that said changes were not consistent with Justice Department recommendations. Hence the request for a consent decree, wherein a judge would approve and monitor a settlement.

In an interview with WMP&I last summer, US Attorney Andrew Lelling did not mention a consent decree, but he did say Springfield and the feds would be negotiating on how to alter course at Pearl Street. A consent decree is an option, one that became more likely under President Joe Biden than it was under Donald Trump.

However, such consent decree would likely happen in federal court. The litigation between Sarno and the Council while related to the Police Department, is in state court. Thus, it is quite separate from the Justice Department report and the demands of PVP and the NAACP.

In his post-argument brief, Sarno’s attorney largely restated his oral argument. An entire section discusses certification language in Springfield’s charter, asserting this proves Sarno can appoint department leadership however he fancies. There is no dispute that the mayor can appoint whoever he wants. The case turns on whether the Council can redefine the department’s leadership structure.

The brief also speeds around a cul-de-sac centered on the state’s contract law for police and fire chiefs. Namely, Sarno’s brief states the Council cannot change department leadership structures because the mayor can contract with whomever he appoints. Yet, the position at issue here had been abolished and replaced with a commission before the incumbent sole commissioner, Cheryl Clapprood, signed her contract.

The Council’s lawyers, in their new brief, observe that courts have long found boards or commissions qualify as a “department”—the same kind the Council can create, abolish or reorganize. They also note the “certificate” section the mayor points to is little more than a record-keeping statute. The Council’s lawyers also turn around the mayor’s claims about the contract law. They note the statute explicitly warns it does not apply to a city or town’s appointment powers.

This, the attorneys argue, is the more harmonious reading alongside the charter. It necessarily includes the Council’s right to define where appointments powers lie—as long as the mayor still appoints the top officials, in this case the Commission.

Perhaps most notably, the Council’s attorneys observe that the mayor has in fact requested changes to leadership ordinances before.

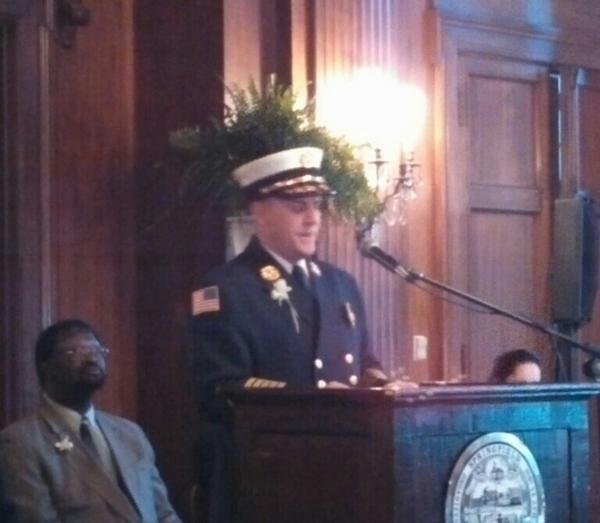

What’s good for a Fire Commissioner not good for a Police Commissioner? Former Commissioner Conant in 2013. (WMP&I)

When Sarno sought to appoint now-former Joseph Conant Fire Commissioner, the mayor asked the Council to revise the ordinance laying down a commissioner’s qualifications to allow Conant’s appointment. The Council passed the bill. Sarno signed an employment contract under the same statute at issue in this case and appointed Conant. In short, Sarno once acknowledged the Council’s authority on department’s structures and consequently sought appropriate legislation.

There is no indication as to when Judge Flannery will rule. Regardless of outcome, an appeal on either side seems likely.

As for the consent decree PVP and the NAACP seek, the city will likely not concur without DOJ pressure. However, the Justice Department and the US Attorney’s office in Massachusetts are in some flux now. Biden’s nominee for Attorney General has yet to receive Senate confirmation. Meanwhile, Senators Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey have announced a search for candidates to replace Lelling.

Still, it is possible Lelling could act assuming he gets a green light from Washington. Sarno has claimed his administration is working closely with Lelling’s office, though the latter has declined comment. After Hampden District Attorney Anthony Gulluni sought information about bad actors at Pearl Street, Lelling demurred, claiming Springfield Police were still under investigation.