Analysis: Amid All the Darkness, Light…Even Hope…

Hope? State Senator-elect Eric Lesser and Attorney General-elect Maura Healey last weekend. (WMassP&I)

There is little doubt that Tuesday was a bad day for Democrats, but something else that shares a number of letters with that party lost by a far greater margin: democracy. Whatever your political perspective, there is nothing to celebrate about the poor turnout, disgust and apathy that led to the results. Certainly those with Machiavellian designs on changing policy may not care. Yet that is not a reason to walk away satisfied with what happened unless that really is more important than ensuring a fair representation of the people are consenting to what leaders promise.

Despite this, however, there is cause to hope that things can be different. In Massachusetts where Democrats overwhelmingly prevailed despite losing the governor’s office, there was manifest proof campaigns of ideas can prevail over a campaigns of fear and loathing. In the election of Maura Healey as attorney general and Eric Lesser to the State Senate, there is a sense that even in this environment exactly that happened.

Both anecdotally and in the poor turnout nationwide, the blasting of negative ads, however sometimes effective, turned voters off completely. While Democrats tried to turnout voters with a historic investment in GOTV, it was likely blunted by the pall cast by ads put up by candidates and third parties alike savaging the other side. Consequently, the lower turnout resulted in an electorate that skews right.

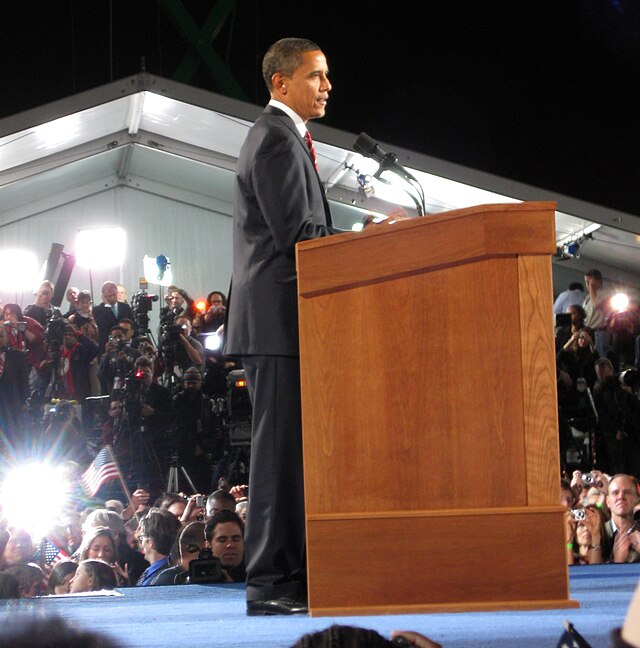

Obama in 2008 after winning the election. Although his political enemies sought to destroy him and his optimistic approach from day one, arguably neither the president nor Democrats did enough to prevent politics from sliding back toward what turns voters off. (via wikipedia)

For example, the Harvard Institute of Politics suggested younger voters, traditionally a mainstay of the Democratic party, were beginning to look elsewhere, including to the Republican party. However, this poll also noted that this phenomenon was largely among youngsters who were very likely to vote. Among all voters, far less had changed. But why were so few interested? Part of it was the decline and arguably the destruction of the optimistic political vision on which Barack Obama rode into office.

It was not just the gridlock, though that felled that movement. It was a failure to properly communicate successes paired with either a backing away from key Democratic values or a failure to properly offer a vision of them. Some effort was made to do this in the midterms, but it probably came too late was lost as ISIS and Ebola stole the stage.

This is not to say that showing the other side for what it is has no role. Unambiguous faults in the candidate, let alone their position are fair game. But overemphasis the minuses either directly or by implication is not effective without the concurrent positive image.

Observers may question how much this applies to either of the campaigns highlighted. Yes, negativity existed in these races, but so did vision and a belief that the process can make a difference. Maura Healey painted a picture, based on her experience, of what her office could do to defend the people of the commonwealth. Lesser, while using some traditional Western Massachusetts political packaging, promoted policies that could turn the tide in the West. Subliminally, those same policies and rhetoric offered a brighter future of a commonwealth closer together.

It is true that thousands of outside dollars were poured onto the head of Lesser’s principal opponent Debra Boronski (though far less than in other such races). Newspaper and radio ads and mailers described—accurately, if also negatively—her positions on several issues. Republicans and allied groups never responded in any meaningful way and what they did only happened within 48 hours of the election.

However, Lesser did not run his campaign in the negative. There were moments in the thrust and parry of debates where he struck Boronski and he and the party did call out what they deemed disqualifying issues with her candidacy. Nonetheless, such efforts were ancillary to his campaign.

Rather, Lesser focused on his overarching theme—a better Western Mass, supported by good policy, to make the region thrive. Boronski, by comparison, offered a nebulous promise of lower taxes and jobs that she could deliver because of her experience—about which she elaborated poorly. Being an under ticket race, there was little either campaign to do to boost turnout, but they could induce more excitement among voters within the district than the gubernatorial air war above.

In several ways Lesser ran a campaign along the outlines of Obama’s first presidential race (and arguably his US Senate race, although his opposition was mostly token then). It worked. In a year when Republicans marched to victory using broad anti-Obama sentiment, a candidate with some of the closest ties to the White House won by an unquestioned margin. Certainly his prodigious fundraising helped, but it would have been for naught if his message did not resonate.

Maura Healey (via Twitter/@maura_healey)

The senate campaign was not a love-fest, but it was substantive and aspirational. The same could be said of Healey’s bid for attorney general. In some ways, the real contest was always the primary, which got quite a bit more heated. Her opponent was practically irrelevant in the general, but in both parts of the contest, Healey largely campaigned with an appeal to the better angels of voters’ nature.

Healey’s campaign was, again, one of ideas and a vision for the office. In the primary, there was no real negativity, except, again in the heat of debates. Both candidates put forward positive ads on television, but Healey made the pitch much better tying in her experience and background.

During the primary and carried over into the general, voters could see the proposals to take on gun trafficking while advocating for criminal justice reform. The latter resonated with poorer communities suffering under the status quo and the wealthier ones who have been fruitlessly paying for it. From civil rights to the environment to financial regulation, there was something for people to latch onto and believe something better is possible.

In the general, although she was not on air, it is not hard to see why Republican John Miller’s ads fell flat. Recycling the largely discredited attack on Martha Coakely about the Department of Children and Families, Miller unsuccessfully tried to tear down Healey as a creature of Beacon Hill.

The point is that Healey offered a vision that not only resonated with voters, but gave them a reason to want to vote and be optimistic about what her election would bring. The substantive, positive, hopeful message won.

Of course, neither race featured a disproportionate lump of money falling on the winner’s head. Thus it is hard to fully compare it to the post-Citizens United environment. Yet, this hopeful note rising above the din should offer us proof that politics can be wielded for the good. There will be a time and a place for the negative, but expecting something better than just that is not Pollyannaish. Politics can and should be about vision and a substantive promise of a brighter future.

Voters might like that and maybe they will tune in.